ROOM 4

Brecht's life after exile.

Information about Brecht's life during his time in exile and his returning to Berlin

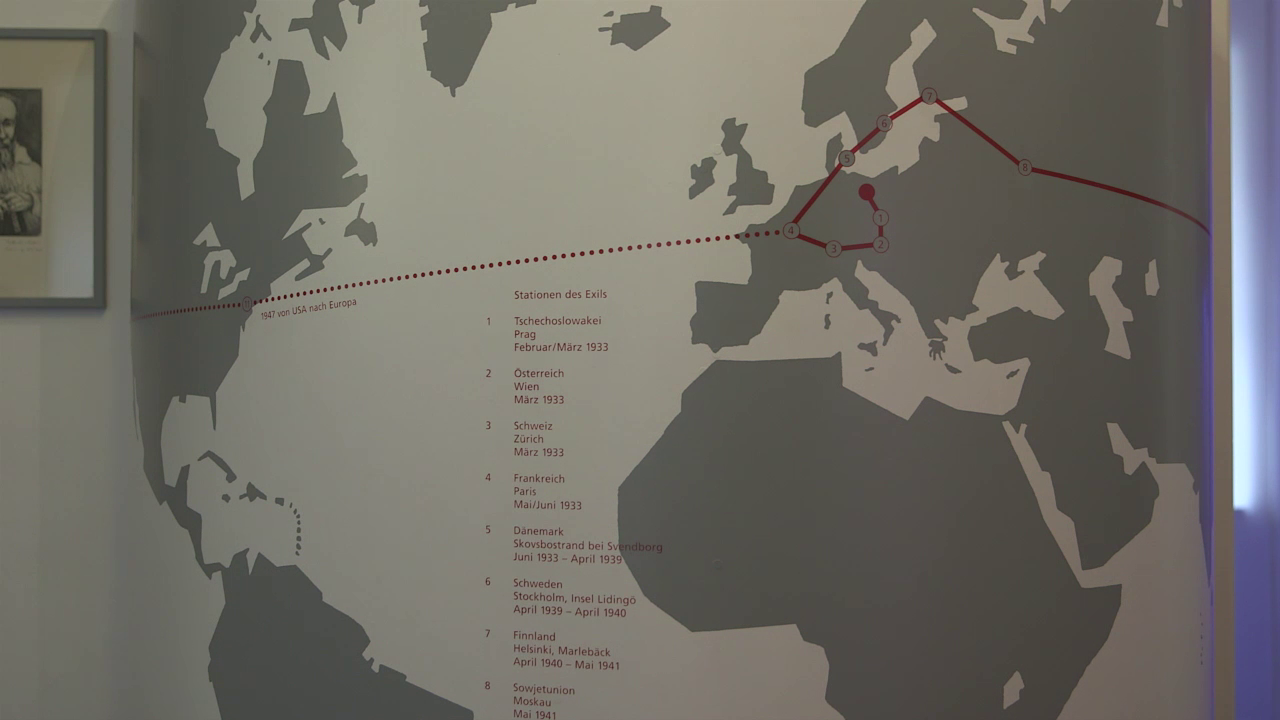

The Nazis arrived and Brecht left. He departed from Germany the day of the Reichstag fire: First he went to Prague and then to Austria. This was the beginning of a migratory life which started out in Europe and would eventually take him all over the world. “I changed countries more than shoes”, he once said – probably an accurate statement.

His journey first took him to Denmark. There he found refuge under a Danish thatched roof. But when the Germans came closer and began occupying Denmark, he travelled to Sweden and then on to Finland. When the German invasion of Finland was impending, too, he left for the United States via Moscow and Vladivostok. It seemed he went directly to heaven – which ended up being hell for many – in other words, to California. He apparently experienced exile quite strongly: He realized that his world had been turned upside down. In the past, he’d been the one sitting while others were queuing to be seen by him. In America, however, he was the one queuing and waiting to be heard; he wasn’t dealt with when it was his turn, but had to wait until everyone else had been dealt with first. A complete reversal of his own feelings and ideals – all of a sudden, he was a nobody.

America: "Land of the Eternal Spring"

He tried to gain a foothold in the American film industry. This proved exceptionally difficult because no one took an interest in what people had been in Germany, but only in what they were capable of being in America. Brecht once said he’d led the existence of a “gold digger” in America. When he met Eisler in Hollywood, Eisler said to him: “This is a country of eternal spring. What one should really write in such a place is elegies.” So Brecht set out to write his Hollywood Elegies – where the world was also upside-down. A country of eternal spring in which he was dissatisfied and saw what many Americans saw: houses with attached garages and nothing else. He suspected – like many others – that there was a price tag on every little olive tree, because he understood that anything can be sold, anything can be bought and that money was the only thing that counted there. His Hollywood Elegies are his most famous works written in exile.

While still in Denmark and Finland, he’d written his Refugee Conversations: a sarcastic reckoning with the Nazis, which was partially biographical. It was sarcastic because he said in it that the most noble aspect of a human being is not being human but having a passport. A human being is easily conceived; obtaining a passport, however, is incredibly difficult. Then he dealt with the Nazis and created two characters representing what was going on in Germany ‒ the so-called order the Nazis were aspiring to establish and which was, in reality, the destruction of human life as the world knew it.

Back in Europe

Brecht in exile: He’d travelled a long way, all around the globe. He eventually left America after being interrogated in New York as he was still under suspicion of being a member of the communist party. Back in Europe, he found it hard to regain his foothold. He first went to Zurich but didn’t stay for long. He hoped to settle down in Austria as his wife had an Austrian passport, and ended up returning to Berlin.

Once Exiled, always Exiled

In a way, it was then that his second exile began. Heinrich Mann once said: “Once exiled, always exiled.” This is also true for Brecht. One of his poems says: “Suitcase still lying on the cupboard”, and there’s another where he’s sitting on the curb not knowing whether he’s coming or going, only that he’s in transit. This existence as a refugee who forever remains a refugee inside finds expression in his theatrical work, too. His time at the Berliner Theater was like being on an island – if one could put it that way. He wrote the Buckower Elegies, which also dealt with continued exile. In a way, exile means no longer being fully at peace with yourself. One’s own identity has been partially lost. Brecht travelled back in history and said: “My destiny is the same as Homer’s; as that of the ancient poets; the one Heiner had, and I, Brecht, who took refuge under a Danish thatched roof.” He legitimised himself to himself by joining ranks with the many persecuted artists who’d undergone the same destiny as he had in the past – that of exile.

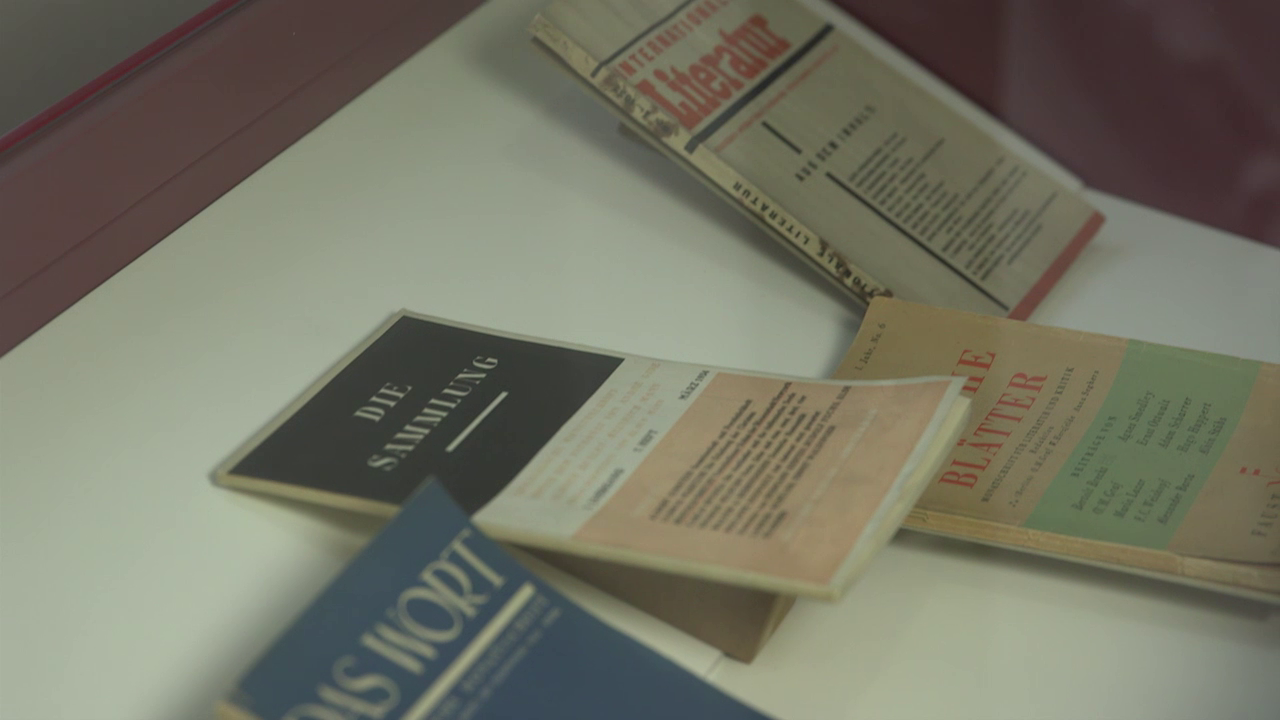

International Literature

It’s important to remember that Brecht was immensely productive while in exile. He wrote prolifically: His major plays, except those from the 1920s, were all written in exile. Although his plays were staged in New York, London and Zurich, too, they remained peripheral phenomena of the literary world. He published his works in various international literary magazines (some of which are on display in this room), including the Moscow-based magazines International Literature and The Word – a magazine also published in New York – as well as magazines in Zurich. He hadn’t completely fallen off the edge of the world and did remain present on the literary scene. During this time of exile in Los Angeles, he “travelled the world”, so to speak, in a literary fashion. This also demonstrates that he wasn’t really oppressed in the countries where he lived and was indeed able to make himself heard. He wrote bitter satires about Hitler and Göring and tried to put right a world that had been turned upside down for him – while always remaining fully himself in the process.

Lifestyle

He never had bad accommodation in the places where he found refuge; in Denmark he lived quite comfortably; in Moscow there was of course no particularly great place awaiting him, but Moscow, in any case, was only a way station on his journey. It was there he lost his friend and colleague in poetry, Margarete Steffin. He owned a respectable house in Los Angeles (which, up until a few years ago, was open to the public). His fate was different from others who were completely impoverished and forced to stand in the streets selling their own books to survive. We have no detailed knowledge about how he sustained himself. What we do know, however, is that he was a smooth operating Swabian who always knew how to find his way around his world of exile. Even so, he found America genuinely dreadful and was glad to be able to leave it behind him. It wasn’t Europe and the world he’d grown up in. His journey through exile had many stops along the way; he lost a great deal, but gained quite a bit, too. What he never gave up was his personal freedom. He employed his Swabian wit to break down his political persecutors in America. In the McCarthy era, when the communist witch hunt was chasing after all foreigners – including Brecht of course ‒ he fought back with cunning and malice, and got away with it.

Conclusion

“Brecht in exile” is an intriguing and multifaceted topic. One can only hope that the time he was outside Germany will not be forgotten inside Germany. It’s an important epoch of his life and I feel it may be what made him so immensely prolific. Of course, we may wonder what would have happened if he’d stayed in Germany. He would certainly have remained at the theatre, and Berlin would have been a wonderful stage for him, too. But exile made him and many others stronger: The Nazis wanted to break him, but they couldn’t. “Once in exile, always in exile.” This may be easier to understand if we remember the waves of human exile which engulfed Europe after Brecht’s time. The exile that chased him around the world, however, was an unusual one and he knew how to make the best of it. It’s his works from that era which will have the greatest lasting power. One such work is Puntila – among the last of his major plays. In it, two characters represent two sides of the same split existence. This experience of division, the “self” that’s both here and there, that’s accepted here and rejected there, is one experienced by most people who are forced into exile.